If you tried it today, you might be arrested. But back in the 1930s and '40s it was not uncommon for men to photograph you walking down the street.

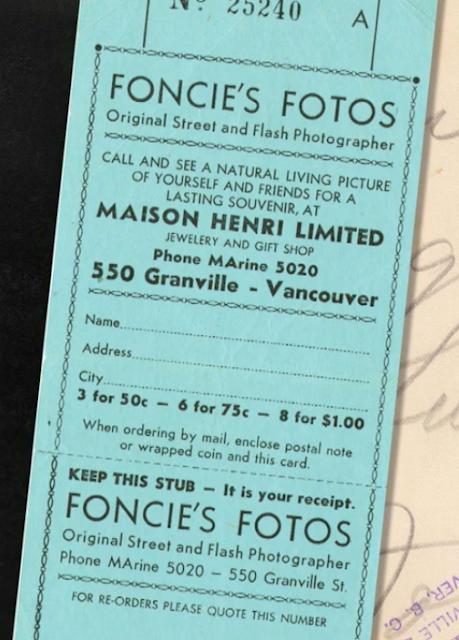

The practice of sidewalk or street photography really began in the thirties, when money was scarce and photographers had to get creative to earn a living. Setting up on a busy street, they snapped photos of people walking down the sidewalk. Subjects would be given numbered tickets in the hope that they would agree to buy prints.

A claim tag from Foncie's Fotos

Hazel Stevens with niece Marlene (b. 1940), in a typical "walking picture" taken by a street photographer, late 1940s.

Aunt Annie Fraser (Pete Fraser's sister) with her great-nephew Murray Holden (b. 1942), on a shopping trip to Winnipeg.

The five-minute walk along Portage Avenue between Eaton's and the Hudson's Bay department stores would have been prime territory for Winnipeg street photographers. Most were candid shots, but some photos were by request. During the war, servicemen bought portraits of themselves in uniform, and wanted photos of their sweethearts as keepsakes.

Edmund Stevens and his mother Zelma.

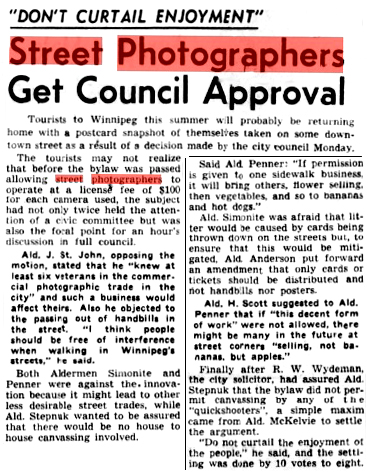

The practice was not as ad hoc as it sounds. Street photographers were subject to by-laws and restrictions. Municipal councils debated whether to allow them at all. Many politicians and citizens considered them a low-class nuisance, and wanted their numbers kept in check.

Winnipeg Free Press, January 22, 1947.

John Glover was a Winnipeg street photographer who often had to defend his business.

Winnipeg Free Press, August 17, 1944

Street photographers were not allowed within 50 feet of any established studio, and could work in certain areas only. Tripods on sidewalks were not allowed, as they took up space and were a tripping hazard. Photographers could be fined for littering if their subjects tossed their tickets away.

The draft bylaw was much debated and received notice in the city papers.

Winnipeg Free Press, February 13, 1947

Winnipeg Free Press, February 25, 1947

The 1947 Winnipeg bylaw allowing street photography barely passed, and required photographers to pay a hefty licence fee of $100 for every camera used. With low margins, the fee was enough to discourage some.

Winnipeg Tribune, February 25, 1947.

Although approved, there was fear that allowing street photography would lead to other "less desirable street trades" like selling flowers, vegetables and hot dogs.

Winnipeg Free Press, September 10, 1947

John Glover could practice, but was charged with littering.

Winnipeg Tribune, September 10, 1947

1947 was a tough year for Winnipeg "snapshot men." The two daily papers both reported the $10 littering fines.

Winnipeg Free Press, July 17, 1947

John Glover's request to shoot candid photos in two city parks was denied.

Street photography garnered much attention in the 1947 newspapers, often for the related politics and hassles, but it was a teeming fad none-the-less. Ted Schrader of the Winnipeg Tribune noted that "about 15,000 pictures are snapped on the streets each day, and of these, 5,000 are printed. There are seven different companies operating along Portage Ave. and Main St., employing 12 photographers." His column explained the business:

Winnipeg Tribune, July 11, 1947.

John Glover finally gets some positive press and a little understanding.

Not everyone discouraged or disliked street photography, and they existed in cities around the world, often chasing the tourist trade. In Winnipeg there was enough business for dedicated practitioners to earn a modest living, at least in warmer months. And newspaper stories weren't always negative. The Winnipeg Tribune and the Winnipeg Free Press both picked up a story from Lethbridge, Alberta, about how a claim tag in a lost coat's pocket provided a clue to the owner.

Winnipeg Tribune, June 14, 1952

In another case, a Montreal thief was apprehended because of a claim ticket found at the scene:

Winnipeg Free Press, February 15, 1947

Street photography disappeared over time. It was banned in Toronto in 1954 and in tourist areas in Paris in 1969.

The 45-year career of Vancouver photographer Foncie Pulice was longer than most. He took about 15 million photos between 1934 and 1979. The Museum of Vancouver profiled him in a 2013-14 exhibit entitled Foncie's Fotos that gives us insight into the profession. It encouraged viewers to dig out their own Foncie photos from family albums.

Today street photography means something quite different, more akin to photojournalism or documentary photography. Photographers try to capture nitty gritty city life, rather than happy portraits of passersby. Digital technology has made photography instant and accessible, but serious photographers scoff at the amateur cliches, like reflections in puddles, homeless people, old fire escapes, and pointless photos that are supposed to be edgy.

Back to Top ↑